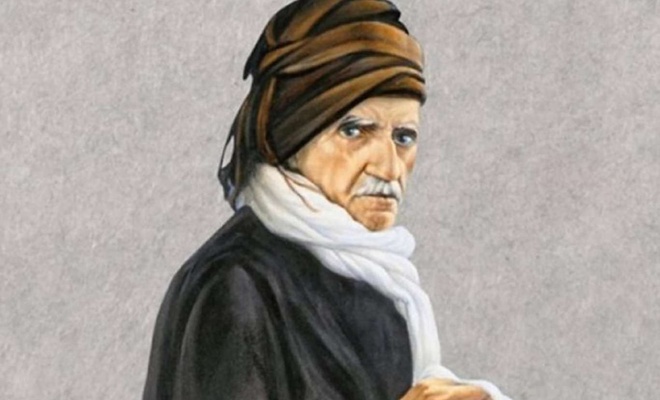

Bediuzzaman Said Nursi commemorated on the 61st anniversary of his death

Said Nursi, who is commonly known with the honorific Bediüzzaman (meaning “wonder of the age”), or simply Üstad was a Kurdish Islamic Scholar who wrote the Risale-i Nur Collection, a body of Qur'anic commentary exceeding six thousand pages.

Google News'te Doğruhaber'e abone olun.

Google News'te Doğruhaber'e abone olun. Believing that modern science and logic were the way of the future, he advocated teaching religious sciences in secular schools and modern sciences in religious schools. Nursi inspired a religious movement that has played a vital role in the revival of Islam in Turkey and now numbers several millions of followers worldwide.

He was able to recite many books from memory. For instance: “So then he (Molla Fethullah) decided to test his memory and handed him a copy of the work by Al-Hariri of Basra (1054–1122) — also famous for his intelligence and power of memory — called Maqamat al-Hariri. Said read one page once, memorized it, then repeated it by heart. Molla Fethullah expressed his amazement.

Said Nursi was born in the Kurdish village of Nurs near Hizan in the Bitlis Vilayet of the Ottoman Empire, in Kurdistan. He received his early education from scholars of his hometown, where he showed mastery in theological debates. After developing a reputation for Islamic knowledge, he was nicknamed “Bediuzzaman”, meaning “The most unique and superior person of the time”.

He was invited by the governor of the Vilayet of Van to stay within his residency. In the library of the governor, Nursi gained access to an archive of scientific knowledge he had not had access to previously. Said Nursi also learned the Ottoman Turkish language there. During this time, he developed a plan for university education for the Eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire. By combining scientific and religious (Islamic) education, the university was expected to advance the philosophical thoughts of these regions.

However, he was put on trial in 1909 for his apparent involvement in the Ottoman countercoup of 1909 against the liberal reform movement named the Committee of Union and Progress, but he was acquitted and released.[36] He was active during the late Ottoman Caliphate as an educational reformer and advocate of the unity of the peoples of the Caliphate. He proposed educational reforms to the Ottoman Sultan Abdul Hamid aiming to put the traditional Madrasah (seminary) training, Sufism (tasawwuf) and the modern sciences in dialogue with each other.

During World War I, Nursî was a member of the Ottoman Empire's “Special Organization”. In January 1916 he was captured by Russian forces and taken to Russia as a prisoner of war, where he spent over 2 years. He escaped in the spring of 1918 and made his way to Istanbul. His return was welcomed and he was chosen to be a member of Dar-al Hikmat al-Islamiye, an Islamic academy seeking solutions for the Islamic world’s growing problems.

Nursi was a worrying-enough influence for the incipient leader of the Turkish Republic, Mustafa Kemal Atatürk, to deem it necessary to seek to control him by offering him the position of ‘Minister of Religious Affairs for the eastern provinces of Turkey, a post that Nursi famously refused. This was the beginning of his split from the Kemalist circle. Conversely, the secular government in the Republic of Turkey would later stigmatize his attempts to renew traditional faith. Modernization of intellectual culture in Anatolia thusly bifurcated along two approaches: assimilation of occidental understanding; and functionalization of extant liturgics. Nursi was the major contributor to the latter approach, and his early life as a memorization savant enabled him to use scripture for teaching with mnemonic metaphor. Friction between the two spheres of thought led to breakdowns of civility and the eventual reclusion of Nursi.

After arriving in Istanbul, Said Nursi declared: “I shall prove and demonstrate to the world that the Quran is an undying, inexhaustible Sun by updating it to meet modern life requirements!”, setting out to write his comprehensive Risale-i Nur, a collection of Said Nursi's own commentaries and interpretations of the Quran and Islam, as well as writings about his own life.

Said Nursi was exiled to the Isparta Province for, amongst other things, performing the call to prayer in the Arabic language.

After his teachings attracted people in the area, the governor of Isparta sent him to a village named Barla where he wrote two-thirds of his Risale-i Nur. These manuscripts were sent to Sav, another village in the region, where people duplicated them in Arabic script (which was officially replaced by the modern Turkish alphabet in 1928).

After being finished, these books were sent to Nursi's disciples all over Turkey via the “Nurcu postal system”. Nursi repeatedly stated that all the persecutions and hardships inflicted on him by the secularist regime were God's blessings and that having destroyed the formal religious establishment, they had unwittingly left popular Islam as the only authentic faith of the Turks.

Unlike peasant women, Said Nursi believed that the face and hands of urban women should be covered under the Quran's command to cover up.

Besides these writings themselves, a major factor in the success of the movement may be attributed to the very method Nursi had chosen, which may be summarized with two phrases: 'mânevî jihad,' that is, 'jihad of the word' or 'non-physical jihad', and 'positive action.'

Nursi considered materialism and atheism and their source materialist philosophy to be his true enemies in this age of science, reason, and civilization. He combated them with reasoned proofs in the Risale-i Nur, considering the Risale-i Nur as the most effective barrier against the corruption of society caused by these enemies. In order to be able to pursue this 'jihad of the word,' Nursi insisted that his students avoided any use of force and disruptive action. Through 'positive action,' and the maintenance of public order and security, the supposed damage caused by the forces of unbelief could be 'repaired' by the 'healing' truths of the Quran.

Said Nursi lived much of his life in prison and in exile, persecuted by the secularist state for having invested in a religious revival.

Alarmed by the growing popularity of Nursi's teachings, which had spread even among the intellectuals and the military officers, the government arrested him for allegedly violating laws mandating secularism and sent him to exile. He was acquitted of all these charges in 1956.

In the last decade of his life, Said Nursi settled in the city of Isparta. After the introduction of the multi-party system, he advised his followers to vote for the Democratic Party of Adnan Menderes, which had restored some religious freedom. Said Nursi was a staunch anti-Communist, denouncing Communism as the greatest danger of the time. In 1956, he was allowed to have his writings printed. His books are collected under the name Risale-i Nur (“Letters of Divine Light”).

He died of exhaustion after traveling to Urfa. He was buried in a tomb opposite the cave where Prophet Ibrahim (Abraham) is widely believed to have been born.

After the military coup d'état in Turkey in 1960, a group of soldiers opened his grave and buried him at an unknown place near Isparta during July 1960 in order to prevent popular veneration. (ILKHA)