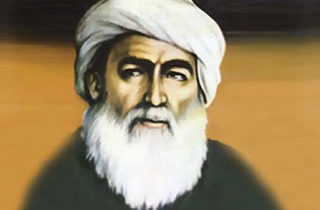

Sheikh Said, a revered Kurdish Islamic scholar, was sentenced to death by the Independence Tribunal of the Turkish Republic on June 28, 1925, and executed the following day.

During the Ottoman Empire, the Caliphate united diverse communities under the Islamic banner, fostering ethnic and cultural diversity through a policy of recognition and tolerance. However, the abolition of the Caliphate weakened the religious ties between Kurdish and Turkish Muslim communities, causing discontent among Kurds who vehemently opposed the new state system based on Western principles of republicanism, nationalism, and secularism.

Sheikh Said, who held a prominent position as the chief of the Naqshbandi Islamic Order in the Palu district of Turkey's eastern Elazığ province, wielded great influence in the region due to his lineage tracing back to Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). The elimination of religious institutions, part of Mustafa Kemal's efforts to replace Islam, ignited Kurdish dissent against state authorities.

The uprising began when several soldiers of the gendarmerie mistreated women during a tribal wedding in a village in Diyarbekir (present-day Diyarbakır) in early 1925, prompting local youth to retaliate against the soldiers. The military station commander sought Sheikh Said's assistance in apprehending the perpetrators. However, Sheikh Said, recognizing the potential for escalation, explained that all tribes were gathered for the wedding. Despite his assurances, his stance was deemed rebellious.

The clash between Sheikh Said's followers and a gendarmerie platoon in the village of Dicle, Diyarbakir Province, on February 13, 1925, ignited a widespread uprising that rapidly expanded. Sheikh Said, having captured the governor and other officers, sought to unite the movement under a single center, issuing a declaration urging people to rise up in the name of Islam. The rebellion was initiated in defense of Islamic Sharia.

With the support of tribes from Mistan, Botan, and Mhallami, Sheikh Said advanced toward Diyarbakır via Genç and Çapakçur (now Bingöl), capturing the cities of Maden, Siverek, and Ergani. Simultaneously, another uprising led by Sheikh Abdullah moved toward Muş via Varto. However, the forces that had taken control of Varto were eventually defeated and forced to retreat. On February 21, the government declared martial law in the eastern provinces. Subsequently, the army sent troops to confront the insurgents on February 23, but they were compelled to retreat to Diyarbakır against Sheikh Said's forces. The following day, a separate uprising under the leadership of Sheikh Sharif briefly held control over Elazığ.

In early March, approximately 10,000 fighters led by Sheikh Said launched an attack and laid siege to Diyarbakır. Despite continuous supplies to the besiegers, the garrison, led by Mürsel Pasha, successfully repelled the attacks. However, with the help of Kurdish residents, a group managed to infiltrate the city, which the garrison discovered. Following intense clashes between March 7 and 8, the group was defeated, and only a few individuals managed to escape. Realizing that the siege was failing, Sheikh Said lifted the blockade and withdrew his forces from Diyarbakır.

On February 13, 1925, Sheikh Said addressed the people in his sermon at the Piran Mosque, expressing his concerns over the closure of religious institutions, the abolition of the Ministry of Religion and Foundations, and the insults against the Prophet Muhammad by certain irreligious writers in newspapers. Sheikh Said also issued various declarations against those who opposed him, signing them as "Emir’ül Mücahidin Muhammed Said El-Nakşibendi." Letters were sent to Alevi Zaza tribal chiefs, Kurdish beys, network and tribal leaders, and Turkish gentlemen and aghas in Ergani, inviting them to join a collective struggle against the Kemalist rule.

The Independence Tribunal in Diyarbakır, on June 28, 1925, sentenced Sheikh Said and 47 other Islamic scholars to death. The sentences were carried out the following day, with Sheikh Said being the first to face execution. In total, over 7,000 individuals were prosecuted by the Independence tribunals, and more than 600 people were executed.

Following the uprising, the Turkish state devised the Report for Reform in the East (Şark Islahat Raporu) in 1925, which proposed Turkification measures for the Kurds. Consequently, thousands of Kurds fled their homes in southeastern Turkey and sought refuge in Syria. The period was marked by a significant loss of life, with hundreds of villages pillaged by soldiers and numerous families exiled to western provinces of Anatolia.

As we commemorate the 99th anniversary of the martyrdom of Sheikh Said and his companions, it serves as a poignant reminder of the historical events that shaped the Turkish Republic and the complex dynamics between religion, culture, and state during that transformative period. (ILKHA)

Dünya

Dünya

Güncel

Güncel

Spor

Spor

Güncel

Güncel

Güncel

Güncel

Güncel

Güncel

Dünya

Dünya

Dünya

Dünya

Güncel

Güncel

Güncel

Güncel